Continued from the previous entry

In this post, I’ll show you what my work flow generally looks like for reverse engineering. In the past, I’ve worked on a few reverse engineering projects like the Broadcom BCM43xx and the Collie SD Card interface for Zaurus. In any reverse engineering project, the first thing to figure out is where to begin! For this post, I’ll take a stubbed function from the ResidualVM code, explain how to find the original implementation, figure out what it does and then re-implement it.

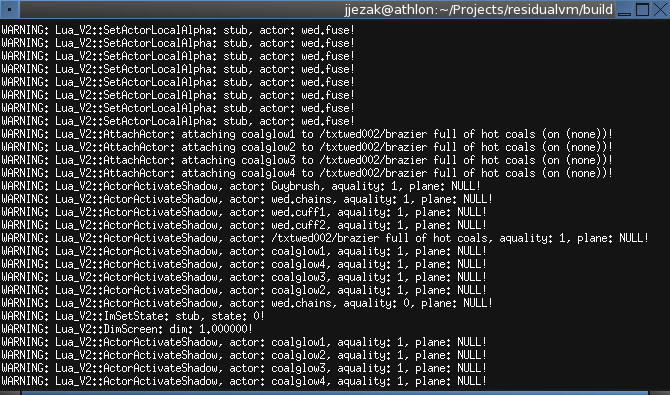

After getting EMI running, I noticed that there were a lot of debug messages about stubbed functions in the console window.

Picking one at random, I decided to look into the function Lua_V2::SetActorLocalAlpha, but first, I needed to do a little bit of research!

Understanding what the structure of the program is before diving into the assembly is usually a good idea. From the documentation at the ResidualVM wiki, I saw that Lua was the scripting language running the game and that EMI’s engine was structurally similar to the one used in Grim Fandango. Let’s take a quick look at the source code for ResidualVM and investigate the structure some more.

In engines/grim/emi/lua_v2.h (line 39), we can see the list of Lua script functions that the engine provides. The actual code that implements these functions can be found in the rest of the files in engines/grim/emi/. Of note, the function we’re interested in, SetActorLocalAlpha can be found in engines/grim/emi/lua_v2_actor.cpp at line 38. Helpfully, this code is partially completed, waiting to be finished!

So, to summarize what we have so far:

- We have identified the function we’d like to work on

- We have information about how the EMI engine was put together

- We have found where the implementation will go once we’ve written it, and some helpful information from the stub function.

Next, we’ll take a look at the binary from the original version of EMI. I’ll be working with the patched version if you’d like to follow along.

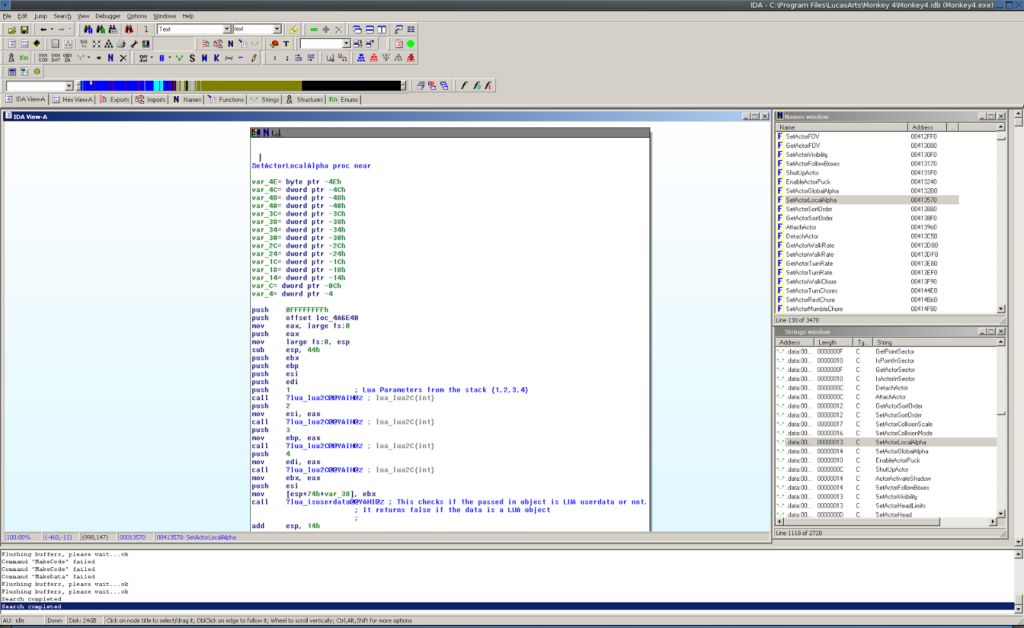

I like working with IDA, it’s a great reverse engineering tool! Luckily for poor students like me, a version of the tool is provided for free for non-commercial use. While all of the features of later versions would be nice, including a native Linux build, this will do for now. If you’re not using windows, Wine can be used to run IDA with almost no issues.

To begin with, I first checked to see if the function name we were interested in was in the executable at all. Some binaries are stripped or obfuscated, making this job a lot harder.

- strings Monkey4.exe | grep SetActorLocalAlpha

This returned two instances:

SetActorLocalAlpha SetActorLocalAlpha: Actor isn't wearing any primitives!

This looked promising! I put the Monkey4.exe binary into IDA and let it process the file. Once this was complete, I searched for the text SetActorLocalAlpha. Lucky for us, there’s a jump table with the function name in ASCII, likely for the Lua scripting engine to convert the text into the actual function call. The entry for SetActorLocalAlpha is found at 0x004C06D8, and points to a function call at 0x00413570. We now have the entry point for the function we’re interested in!

In the next post, we’ll investigate what can be learned from the Lua scripts that actually call this function and how it can be used to improve our code.

In the next post, we’ll investigate what can be learned from the Lua scripts that actually call this function and how it can be used to improve our code.